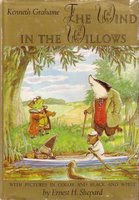

Saturday was an ideal day to read. The snow began at mid-morning and continued throughout the day. With no desire to venture out, and absent a reason to do so, I completed my sixth book of ’05, Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows. I enjoy Ernest Shepard’s illustrations more than I do the text.

Saturday was an ideal day to read. The snow began at mid-morning and continued throughout the day. With no desire to venture out, and absent a reason to do so, I completed my sixth book of ’05, Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows. I enjoy Ernest Shepard’s illustrations more than I do the text.Perhaps I’d find the Willows more endearing if I had read it as a child. I didn’t. I first read the book during the summer before my senior year in high school. On re-reading I discover two odd passages that detract from the overall work. The oddest passage is found in Chapter 7, “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.” It sounds like a short story by Robert E. Howard. Mole and Rat are in search of Otter’s missing child. They find the child asleep at the feet of Pan, a pagan god of the woods.

Pan isn’t named, but he is well-described; his curved horns, hooked nose, his pan-pipes and hooves. His presence, his music, have a narcotic effect upon Mole and Rat who “crouching to the earth, bowed their heads and did worship.” Am I alone in finding this odd? It’s not that I expect Grahame’s forest animals to be Christians or Muslims or Jews, but the introduction of a pagan god into a children’s tale written in early 20th Century England seems strange.

The other odd passage is found in Chapter 9, "Wayfarers All", in which Rat meets a sea-faring Rat, who describes the pleasures of the wandering life and invites Rat to join him on his journey south. Rat succumbs to the spell, but his wanderlust is broken by the steadfast Mole who drags him into his hole, throws him down and holds him captive until the fit passes.

In and of itself, the Sea Rat is not an unusual character, but the extended descriptions of the Grecian Islands, Venice and Corsica seem out of place within the narrow boundaries of the world inhabited by Grahame’s woodland creatures.

Finally, I object to the way the animals and humans casually intermingle. I don’t mind tales of talking animals who dress like humans and drive motor cars. Such books depend on an internal logic to which the author must be true. If, as in Grahame’s case, the internal logic isn’t rigorously observed, the work does not hold together. We see the man behind the curtain.

Humans keep cats and dogs as pets, but interact with Toad as if he were an equal. He escapes prison disguised as a washerwoman. I love Shepard’s illustration, but how tall is Toad? I don’t think it takes an especially bright child to wonder about this scene.

Later, Toad accepts a bowl of stew from a gypsy. The stew is made with partridges and pheasants, chickens and hares, rabbits and peahens. It seems cannibalistic of Toad to so heartily enjoy this repast.

I make too much of nothing, perhaps. Such are the dangers of the study of English literature (and of re-reading a book after so many years). My favorite passages in the Willows are the domestic scenes: The lengthy description of Badger’s home after Mole and Rat seek refuge there from the snowstorm and the dangerous denizens of the Wild Wood, and the passage when Mole returns to his own home after a lengthy absence.

###

I am more than 200 pages into Jared Diamond’s Collapse. It is an interesting and worthwhile book, but reads too much like a textbook. Diamond’s lectures are far more approachable and entertaining than his written work.

No comments:

Post a Comment